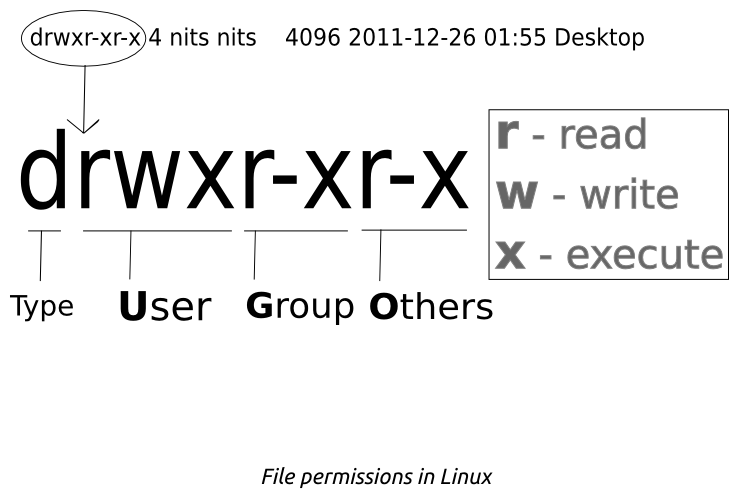

class: center # Command Line  [http://pjb3.me/bewd-command-line](http://pjb3.me/bewd-command-line) .footnote[ created with [remark](http://github.com/gnab/remark) ] --- # Commands The program that runs inside Terminal and allows you to enter commands is called a "shell" The default and most commonly used shell on Unix-based OSes (Mac/Linux) is called "bash" .terminal prompt command -s --option argument1 argument2 The prompt usually has your current directory and ends with a `$` characters, but it can be customized Switches are one letter and start with one hyphen Options are multiple letters and start with two hyphens Each command is actually a separate program, not part of bash Unix-based OSes come with a standard set of programs You can install additional programs or write your own and use them in bash The following slides cover some commonly used commands Bash is a programming language and has things common to all programming languages, such as commands, strings and variables In all of the following examples, when there is a `$`, that means you should type the following command **not** including the `$` at the command-line prompt. Other lines are the output of the command. --- # echo If you want to print something out, you use `echo`. You put what you want printed between quotes: .small[ .terminal $ echo 'Hello, $USER' Hello, $USER ] The text between the quotes is called a **string**, because it is a set of characters strung together. The concept of a string exists in every programming language. Since we used single quotes, the string was printed out exactly as we typed it in. Let's see what happens when you use double quotes: .small[ .terminal $ echo "Hello, $USER" Hello, paul ] This time, the value of the variable called `USER` was printed out. When you have a `$` sign in front of some letters, when you use a double-quoted string, the value of the variable included in the output, instead of the literal text. You can also leave out the quotes and just print the value of the variable directly: .small[ .terminal $ echo $USER paul ] If you leave out the `$`, it will output just the literal string: .small[ .terminal $ echo USER USER ] So you actually don't need quotes at all if you are printing out a string that has no spaces or other special characters. So how do you know what all the current variables are? --- # env In Bash, the variables are stored in your *environment*. You can use the `env` command to print out all the variables that are set and their value: .small[ .terminal $ env TERM_PROGRAM=iTerm.app TERM=xterm SHELL=/bin/bash TMPDIR=/var/folders/0q/x3mx7qv93wddwpvz69p88l3h0000gn/T/ USER=paul PATH=/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/X11/bin:bin PWD=/Users/paul/dev/back-end-web-development EDITOR=subl -w LANG=en_US.UTF-8 PS1=$ HOME=/Users/paul ... ] There is a lot of stuff, so I've truncated the output. We'll talk about some of these variables soon and what they do, but first, let's make it easier to read this output --- # sort In Unix, if you want to modify the output of a program, you can pipe the output of one command into the input of another, using the `|` *(pipe)* character: .small[ .terminal $ env | sort EDITOR=subl -w HOME=/Users/paul LANG=en_US.UTF-8 PATH=/usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/usr/X11/bin:bin PS1=$ SHELL=/bin/bash TERM=xterm TERM_PROGRAM=iTerm.app TMPDIR=/var/folders/0q/x3mx7qv93wddwpvz69p88l3h0000gn/T/ USER=paul ] `sort` is a command that prints each line of its input in alphabetically order. By using the `|`, we are piping the output of `env` to the input of `sort` and then we see the output of `sort` printed out. This is helpful, but if what if we want to see the value of a specific variable, rather than look though the whole sorted list? --- # grep .small[ .terminal $ env | grep USER USER=paul ] In this example, we are using pipe again, but this time to pipe the output to a command called `grep` `grep` will search through its input and only print the lines that match the string you give it. Grep is definitely an odd name, google it if you are interested in the origin. --- # pwd One of the main reasons for using the command-line is for working with files When you are in a bash shell, you are always *in* a directory (a.k.a folder) of your computer. The directory you are in is refered to as your **working directory**, or **current working directory**. Use the `pwd` command to see what directory you are currently in: .small[ .terminal $ pwd /Users/paul ] This is my home directory and using the default configuration of your Terminal and bash, you will start in your home directory `pwd` stands for **p**rint **w**orking **d**irectory. --- # ls list the contents of a directory with `ls`: .small[ .terminal ~ $ ls Applications Documents Dropbox Movies Pictures VirtualBox VMs certs dotfiles ls Desktop Downloads Library Music Public bin dev lb src ] use -l for the long format .small[ .terminal ~ $ ls -l total 0 drwx------ 3 paul staff 102 Jan 20 2013 Applications drwx------+ 19 paul staff 646 Sep 6 16:26 Desktop drwx------+ 34 paul staff 1156 Aug 26 21:36 Documents drwx------+ 165 paul staff 5610 Sep 4 10:46 Downloads drwx------@ 17 paul staff 578 Aug 14 19:30 Dropbox drwx------@ 52 paul staff 1768 Jun 5 11:48 Library drwx------+ 4 paul staff 136 Aug 14 19:29 Movies drwx------+ 6 paul staff 204 Aug 14 19:29 Music drwx------+ 17 paul staff 578 Aug 24 14:15 Pictures drwxr-xr-x+ 4 paul staff 136 Aug 14 19:29 Public drwx------ 5 paul staff 170 Dec 30 2012 VirtualBox VMs drwxr-xr-x 3 paul staff 102 Aug 20 15:10 bin drwxr-xr-x 42 paul staff 1428 Sep 6 16:08 dev drwxr-xr-x 13 paul staff 442 May 16 07:09 dotfiles drwxr-xr-x 4 paul staff 136 Mar 24 04:05 src ] --- # Paths On all Unix-based OSes, including Mac OS X, all files and folders on your computer are stored in a hierachical tree structure. There is only only top-level directory and it is called the *root directory* and it is represented with just `/` characters. For any file or folder (a.k.a directory) on your computer, the location that is stored at is called a *path*, because it represents the path through the tree of directories that you must go through to get to the file. A path looks like this: .terminal /Users/paul/something.txt The directories in the path are separated by `/` *(forward slash)* characters. This means that there is a directory called `Users` in the root directory, and in that directory called there is a directory called `paul`, and in that directory there is a file called `something.txt`. --- # brew There is a nifty program that displays the files and folders in a tree structure, but it's not installed by default. You have to use `brew` to install it. If you don't already have brew installed, go to [http://brew.sh](http://brew.sh) to get the one-liner that you paste into your Terminal to install it. The program to view a directory structure is called `tree` and you can install it via `brew` like this: .small[ .terminal $ brew install tree ==> Downloading http://mama.indstate.edu/users/ice/tree/src/tree-1.6.0.tgz ######################################################################## 100.0% ==> make prefix=/usr/local/Cellar/tree/1.6.0 MANDIR=/usr/local/Cellar/tree/1.6.0/share/man/man1 /usr/local/Cellar/tree/1.6.0: 7 files, 116K, built in 2 seconds ] --- # tree Now that you have `tree` installed, you can run it like these to see everything 2 levels down from the root: .small[ .terminal $ tree / -L 2 / ├── Applications │ ├── 1Password.app │ ├── Alfred.app │ ├── Safari.app ├── Library │ ├── Developer │ ├── Frameworks │ ├── Ruby ├── System │ └── Library ├── Users │ ├── Shared │ └── paul ├── bin │ ├── cp │ ├── ls │ ├── pwd │ └── rm └── usr ├── bin └── local ] You will actually see a lot more output than that, this is a trimmed-down version --- # mkdir To create a new directory, use `mkdir`: .terminal $ mkdir bewd If it worked, `mkdir` has no output. You will just be back at the prompt again. If something went wrong, then the error would be printed. --- # cd Change into a directory with `cd`: .terminal $ cd bewd $ pwd /Users/paul/bewd Use `..` as an argument to cd to go back up one directory: .terminal $ cd .. $ pwd /Users/paul Use `cd` with no arguments to go back to your home directory: .terminal $ cd bewd $ pwd /Users/paul/bewd $ cd $ pwd /Users/paul --- # Redirect output into a file We saw early that you can print out a string using `echo`. Similar to the pipe, you can use a `>` greater than symbol put the output of the command into a new file: .terminal $ echo 'Hello, World' > hello.txt Now if you print out the list of files in the current working directory, you will see that a new file has been created: .terminal $ ls hello.txt Output redirection operator does not only apply to `echo` command. You can redirect the output of any command into a file. For example: .terminal $ ls > ls.txt $ ls hello.txt ls.txt We redirected the output of `ls` to a file named `ls.txt`. We then see the file was created. --- # cat You can print the contents of the file with `cat` _(short for concatenate)_: .terminal $ cat hello.txt Hello, World You can append more text to a file using the output redirection append operator `>>`: .terminal $ echo 'Hello, Again' >> hello.txt $ cat hello.txt Hello, World Hello, Again If you use the regular output redirection operator `>`, that will overwrite the contents of the file if it exists: .terminal $ echo 'Hello, World' > hello.txt cat hello.txt Hello, World --- # mv Move or rename a file with `mv`: .terminal $ mv hello.txt hello_world.txt $ cat hello_world.txt Hello, World --- # cp Copy a file with `cp`: .terminal $ cp hello_world.txt hello2.txt $ ls hello_world.txt hello.txt --- # rm Use rm to remove a file .terminal $ ls hello.txt hello_world.txt $ rm hello_world.txt $ ls hello.txt Use the `-r` switch (short for "recursive") to remove a directory .terminal $ cd .. $ rm bewd rm: bewd: is a directory $ rm -r bewd $ ls bewd ls: bewd: No such file or directory Some OSes/settings may also require you to use `-f` to force a directory to be removed if it is not empty --- # history Bash keeps track of what you've done .terminal $ history 18 ls 19 ls -l 20 pwd 21 mkdir bewd 22 cd bewd 23 echo 'Hello' 24 echo 'Hello' > example.txt 25 ls 26 cat example.txt 27 history Use the up and down arrow to retrieve previous commands --- # Path `PATH` is the environment variable to control where commands are found It is a list of paths (directories) separated by `:` colons .terminal $ echo $PATH /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:... When you enter a command, bash checks the first directory in your path and if it finds a file with the same name in that directory, it executes that file. If it does not find a file, then it tries the next directory in your path, and keeps going until it finds one or reaches the end of your path. Since it is possible to have mutliple version of the same command installed, or to install commands in different locations, as we start installing more programs, it is important to understand this concept. --- # tr The contents of the `PATH` variable can be hard to read in its natural `:` separated format. Fortunately we can fix that with the help of another command called `tr`. The `tr` command is used to translate the input and then print the result of the translation in the output. We can convert each `:` in the PATH into a new-line character. This has the result of printing each directory of your path one a separate line, making it much easier to read: .terminal $ echo $PATH | tr : '\n' /usr/local/bin /usr/bin /bin /usr/sbin /sbin --- # which If you want to figure out where a command actually is on your computer, possibly to verify the correct version is being used, you could use the trick we used on the last slide to print out each entry in your path, and then use `ls` to check each directory see if there is a program there, but that is a tedious and error-prone way to do it. Thankfully we have the `which` is a command to do that job for us. Simply run `which` with the name of the program you are looking for and it will output the full path of the program: .terminal $ which ls /bin/ls $ which grep /usr/bin/grep $ which brew /usr/local/bin/brew --- # export When you set a variable, it is not "exported" by default: .terminal $ FIRST_NAME='Paul' $ echo $FIRST_NAME Paul $ env | grep FIRST_NAME $ If a variable is not exported, other programs, such as `env`, are not able to read that variable. Use `export` to export the variable: .terminal $ export FIRST_NAME $ env | grep FIRST_NAME FIRST_NAME=Paul --- # Configuration Files There are some variables that you will want to set or modify every time you start a bash session. To allow for that, bash looks for a file called `.bash_profile` in your home directory when bash starts up. If the file exists, it executes each line of the file. There is a command called `date` that prints out the current time: .terminal $ date Sat Feb 8 15:29:09 EST 2014 Let's append this command to the end of the `.bash_profile` file in your home directory: .terminal $ cd $ echo 'date' >> .bash_profile Now start a new iTerm tab by pressing _cmd + t_. You should see the date printed out. --- # Processes You computer has multiple processes running at the same time You can list them using the `ps` command Use `ps aux` to list "all" processes, show the "user" and show the "eXtra" info Each process has an id Start a program called `irb`: .small[ .terminal $ irb >> ] We'll learn more about what this program is later, but for now, know that it runs forever waiting for you to enter some commands. In a new iTerm tab, combine `ps` with `grep` to find the `irb` process: .terminal $ ps aux | grep irb paul 33629 0.0 0.0 2423356 11:37AM 0:00.00 grep irb paul 33015 0.0 0.3 2472492 11:34AM 0:00.43 irb Use `kill` to terminate a process .terminal $ kill 33015 $ ps aux | grep irb paul 33761 0.0 0.0 2432768 11:38AM 0:00.00 grep irb By default, `kill` asks a process to shutdown. Use `kill -9` to terminate it immediately. --- # Security and Permissions Unix was designed as a multi-user OS, where different people would be logged in to the same system at the same time. To users from interferring with each other, security was built-in. Files, directories and processes are all owned by the user that created them. `ls -l` shows the ownership and permissions of each file: .small[ .terminal $ ls -l drwx------+ 49 paul staff 1666 Feb 6 14:29 Documents drwxr-xr-x+ 5 paul staff 170 Dec 27 11:40 Public ] Here is part of the output from `ls`. In the first column of output is the file permissions. The first character `d` indicates the file is a directory. The next 3 characters 1st column represent the permissions on the file for the user that owns the file. The 3rd column of output shows the owner is `paul`. Since each of these characters are filled in (not a hyphen), that means the owner (paul) as all 3 permissions, which are **r**ead, **w**rite and e**x**ecute. The next 3 characters of the 1st column represent the permissions for any other users in the group the file is owned by. The 4th column shows the group is `staff`. Each user on the system can belong to 1 or more groups. In the case of the `Documents` directory, all 3 characters are a hyphen, indicating users in the group (staff) cannot read, write or execute this directory. However, the `Public` directory has `r-x`, which means the group (staff) can read and execute the directory, but not write to it. The last 3 characters of the 1st column represent the permissions for any other users on the system that aren't in the staff group. --- class: center  From [http://2buntu.com/1076/understanding-file-permissions/](http://2buntu.com/1076/understanding-file-permissions/) --- # Super User On all Unix-based OSes, there is a super user account known as **root**. It is called root because it is typically the user that can modify the files and directories in the root directory. Security restrictions on files and processes do not apply to the super user. The super user can read, write, execute and file and kill any process. If you want to perform as command as the super user, you use the command `sudo`, which is short for **s**uper **u**ser **d**o: .small[ .terminal $ tail /etc/sudoers tail: /etc/sudoers: Permission denied $ sudo tail /etc/sudoers Password: # Uncomment to allow people in group wheel to run all commands # %wheel ALL=(ALL) ALL # Same thing without a password # %wheel ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL # Samples # %users ALL=/sbin/mount /cdrom,/sbin/umount /cdrom # %users localhost=/sbin/shutdown -h now ] `tail` is a command like `cat`, only it only outputs the last few lines of a file. When I first tried to use it, I got a permission denied error. When I used `sudo`, I was asked to enter my own password (as a security percaution), and then the command was executed as the super user, so I did not get a permission denied error. Everything after `Password:` is the contents of the file. --- # Review * **echo** - Print a string * **env** - Print all variables and their value * **sort** - Sort each line of the input * **grep** - Print each matching line of the input * **pwd** - Print the current working directory * **ls** - List the contents of a directory * **mkdir** - Create a new directory * **cd** - Change the current working directory * **cat** - Print the contents of a file * **head** - Print the beginning of a file * **tail** - Print the end of a file, *(-f)* continue printing as the file is appended to * **less** - Print the contents of a file page-by-page * **wc** - Count the lines, words and characters in a file, *(-l)* for just count of lines * **mv** - Move or rename a file * **cp** - Copy a file * **rm** - Remove a file or directory *(-r)* * **history** - List the commands that you previously entered * **tr** - Replace characters in the input and with other characters in the output * **which** - Print the full path to a command * **ps** - List running processes * **kill** - Terminate a running process * **sudo** - Run a command as the root user * **chown** - Change ownership of a file * **chmod** - Change the permissions of a file * **brew** - Install new commands from the Internet * **tree** - Visualize the directory tree * **curl** - Make an HTTP request * **git** - Version control