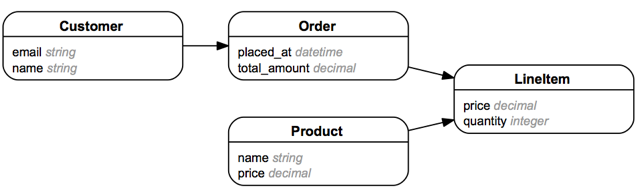

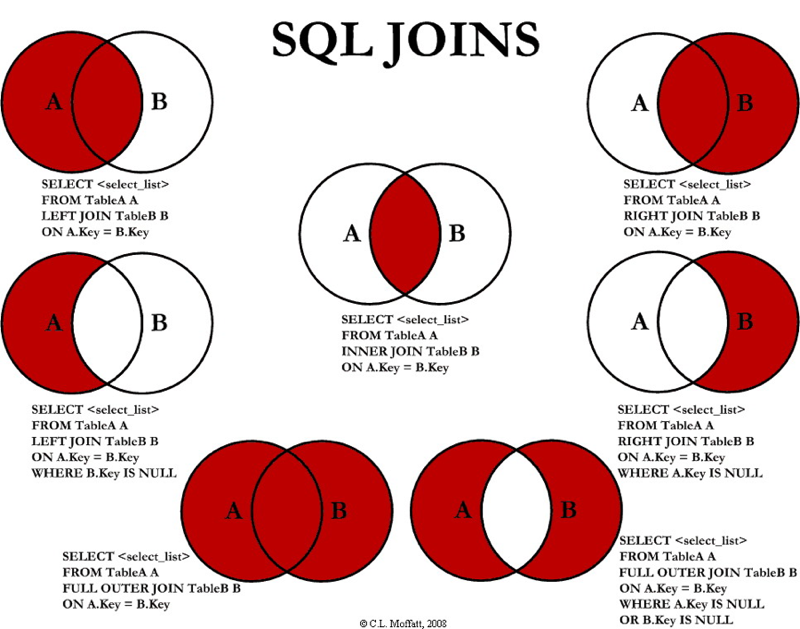

class: middle, center # SQL [http://pjb3.me/bewd-sql](http://pjb3.me/bewd-sql) .footnote[ created with [remark](http://github.com/gnab/remark) ] --- # SQL Structured Query Language (SQL) is a language for querying Relational DataBase Management Systems (RDBMS) tables for data --- # RDBMS A Relational DataBase Management System is a server that stores data in related tables. There are several open source and proprietary RDBMSes, we will use PostgreSQL (often shortened to just Postgres) because it is open source and therefore free, has great features like full-text searching and GIS-related features and is well-supported by Heroku. MySQL is a popular open-source alternative to Postgres and is used for many large web applications including Facebook. SQLite is only for testing and embedded applications. I've used all of these database and prefer Postgres. .center[] --- # Install Postgres.app Mac, use [Postgres.app](http://postgresapp.com/) Make sure to follow the instructions to [setup your path](http://postgresapp.com/documentation/cli-tools.html) If you can run this command, it's working! .terminal $ psql psql (9.3.6) Type "help" for help. paul=# --- # psql `psql` is the command-line tool that comes with Postgres for interacting with your database. It is similar to a bash or irb prompt in that you type commands, it prints the result and waits for you to type the next command. The default prompt in `psql` looks like this: .terminal paul=# That is the name of the database you are connected to followed by an `=` and a `#`. You can can out about what commands you can use within psql using the `help` command: .terminal paul=# help You are using psql, the command-line interface to PostgreSQL. Type: \copyright for distribution terms \h for help with SQL commands \? for help with psql commands \g or terminate with semicolon to execute query \q to quit --- # Create Database To create a database, use the `createdb` command, followed by the name of the database: .terminal createdb betastore To use that database, you can start the psql command in that database: .terminal psql -d betastore Or from within psql you can switch: .terminal paul=# \c betastore You are now connected to database "betastore" as user "paul". betastore=# --- # Tables A table is a like a spreadsheet (or worksheet) in excel, with data organized in rows and columns. .center[] The name of this "table" is "Sheet1". Rows are identified by numbers and columns are identified by letters. --- # Create a Table To start storing data in a table, you first have to create a table. In Postgres, as in all relational databases, instead of referring to the columns by letters, the columns have names. The rows are identified by the primary key. In many apps, the primary key is just an incrementing number. To create your first table, put this into a file named `create_customers.sql` using atom: ```sql CREATE TABLE customers ( id serial primary key, first_name varchar(255), last_name varchar(255), email varchar(255) ); ``` Then from within `psql` run this command to run the query: .terminal betastore=# \i create_customers.sql CREATE TABLE --- # View tables You can view the list of tables with this command: .terminal betastore=# \dt List of relations Schema | Name | Type | Owner --------+-----------+-------+------- public | customers | table | paul (1 row) You can see the structure of one table with this command: .small[ .terminal betastore=# \d customers Table "public.customers" Column | Type | Modifiers ------------+------------------------+-------------------------------------------------------- id | integer | not null default nextval('customers_id_seq'::regclass) first_name | character varying(255) | last_name | character varying(255) | email | character varying(255) | Indexes: "customers_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (id) ] **Tab completion works for file names and table name in psql!** --- # Creating records You create records by using an `insert` statement. Put this into `create_customer_records.sql` in atom: ```sql insert into customers (first_name, last_name, email) values ('Paul','Barry','paul@betamore.com'); insert into customers (first_name, last_name, email) values ('Kyle','Fritz','kyle@betamore.com'); ``` Then run the file from `psql` *(see `\i` from 2 slides ago)* --- # Selecting Records You use a `select` statement to display records: .terminal betastore=# select * from customers; id | first_name | last_name | email ----+------------+-----------+------------------- 1 | Paul | Barry | paul@betamore.com 2 | Kyle | Fritz | kyle@betamore.com (2 rows) Think of a `select` statement as a way to dynamically create a spreadsheet: --- # Displaying Results Vertically As your tables get more complicated, they will have more columns and the output from psql will get hard to read, because it will be so wide that it will be forced to wrap. To make things easier to read, you can change the way the output is displayed to list one column per line. In some cases, this will be an easier way to read the data. The `\x` command toggles your `psql` session between these two modes: .small[ .terminal betastore=# \x Expanded display is on. betastore=# select * from customers; -[ RECORD 1 ]----------------- id | 1 first_name | Paul last_name | Barry email | paul@betamore.com -[ RECORD 2 ]----------------- id | 2 first_name | Kyle last_name | Fritz email | kyle@betamore.com betastore=# \x Expanded display is off. betastore=# select * from customers; id | first_name | last_name | email ----+------------+-----------+------------------- 1 | Paul | Barry | paul@betamore.com 2 | Kyle | Fritz | kyle@betamore.com (2 rows) ] --- # Records A database can have multiple tables and data is organized into tables that relate to each other. A row in a database is often also referred to as a **record**. ## Primary Keys A primary key is a column value that is unique within the table In Rails, this is always a auto-incrementing integer called `id`, as is the case in this example --- # Schema In an RDMBS, you must create the structure of each table before you can create records in the table. You define which columns a table is allowed to have and what the columns are named. We can look at which tables exist in the database using the `\dt` command in `psql`: .terminal betastore=# \dt List of relations Schema | Name | Type | Owner --------+-------------------+-------+------- public | schema_migrations | table | paul public | subscriptions | table | paul Using Rails generators and migrations, we have already created the subscriptions database table. The schema_migrations table was also created by Rails. It is used to keep track of which migrations have already been run. We will cover migrations in more detail in the lesson on Active Record. --- # Database Normalization We should organize our data into tables in a way that minimizes duplication. This process is referred to as **database normalization**. ## First version of our orders table Let's say we are going to create a table to allow us to keep track of orders to our store. We will need the information about who placed the order and what products they ordered. So a naive first attempt at creating at table for this might look like this: .terminal id | customer_name | customer_email | placed_at | products | ---+---------------+--------------------+------------+------------------+ 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-27 | Muffin, Smoothie | 2 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-30 | Smoothie | 2 | John Doe | test@example.com | 2013-09-30 | Muffin, Coffee | ## Problems There are multiple products in the products column, which will make it hard to query. We have also repeated the name of the product in multiple places. Also, the customer name and email are repeated in multiple rows. What are we going to do if a customer wants to change their email address? Or if we rename a product? When designing a database schema, you always want to minimize the duplication of data so that if you need to change a value, you only have to change it in one place. --- # Each column should contain only one value We can create another table called line items to store .terminal orders id | customer_name | customer_email | placed_at ---+---------------+--------------------+----------- 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-27 2 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-30 3 | John Doe | test@example.com | 2013-09-30 line_items id | order_id | product_name | product_price ---+----------+--------------+-------------- 1 | 1 | Muffin | 2.99 2 | 1 | Smoothie | 3.75 3 | 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 4 | 3 | Muffin | 2.99 5 | 3 | Coffee | 3.99 --- # Foreign Keys In the `line_items` table, the `order_id` is called a **foreign key** Foreign keys are commonly used to create relationships between tables .terminal line_items orders ---------- -------------- id id <--- order_id customer_name product_name customer_email placed_at --- # Remove Product Duplication Our `line_items` table was a step in the right direction, but we still have duplication of the product information like name and price. Let's break out `products` into a separate table: .small[ .terminal orders id | customer_name | customer_email | placed_at ---+---------------+--------------------+----------- 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-27 2 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2013-09-30 3 | John Doe | test@example.com | 2013-09-30 line_items id | order_id | product_id ---+----------+-------------- 1 | 1 | 1 2 | 1 | 2 3 | 2 | 2 4 | 3 | 1 5 | 3 | 3 products id | name | price ---+-----------+------- 1 | Muffin | 2.99 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 3 | Coffee | 3.99 ] --- # Relationship Diagram Now the structure of our tables looks like this: .terminal line_items orders ---------- -------------- id products id <--- order_id -------- customer_name product_id ---> id customer_email name placed_at price A table like the `line_items` table is often referred to as a **join table**, because it has foreign keys to both the `orders` table and the `products` table and serves as the link between those two tables. --- # Remove Customer Duplication We still have duplicate customer information, so let's break that out into a separate `customers` table in the same way we did with our `products` table: .terminal customers id | name | email ---+------------+-------------------- 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com 2 | John Doe | test@example.com orders line_items id | customer_id | placed_at id | order_id | product_id ---+-------------+------------ ---+----------+-------------- 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 1 | 1 | 1 2 | 1 | 2013-09-30 2 | 1 | 2 3 | 2 | 2013-09-30 3 | 2 | 2 4 | 3 | 1 5 | 3 | 3 products id | name | price ---+-----------+------- 1 | Muffin | 2.99 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 3 | Coffee | 3.99 --- # Relationship Diagram .terminal line_items orders ---------- customers -------------- id products --------- id <--- order_id -------- id <--- customer_id product_id ---> id name placed_at name email price The `orders` table now has a foreign key to the `customers` table: --- # Denormalization .terminal line_items orders ---------- customers -------------- id products --------- id <--- order_id -------- id <--- customer_id product_id ---> id name placed_at quantity name email total_amount price price In an e-commerce system like the one we are building prices of products will undoubtedly change over time. We need to keep a record of the price of the a customer paid for a product when they placed the order. To support this, a technique called **denormalization** is useful. Denormalization is the opposite of what we just did. It is the process of putting data in multiple places. In this case, we are going to store the price of a product with the line item, for historical purposes. The price in the line items table will not be changed if we change the price of a product. This makes it a good candidate for denormalization because there is still only one place we have to make a change if the price of a product changes. Another reason to denormalize is to improve performance. Let's say we want to sort all orders by their total amount. We could calculate the total amount for each order and then sort them, but that might be slow once we have a lot of orders. Since the total amount of an order doesn't change, we can calculate it once when the order is placed and then save it into a column on the order. **This type of performance-improvement-based denormalization should only be used once you are sure you need it**. It is a mistake to do this when you are first creating your application because you don't even know yet if you will need to sort orders by their total amount. --- # Entity-Relationship Diagram Here is the final structure of our database tables: .center[] This type of diagram is often referred to as an Entity-Relationship Diagram, or ERD for short --- # Exercise: Creating Tables So we want to create our tables so they look like this: .terminal line_items orders ---------- customers -------------- id products --------- id <--- order_id -------- id <--- customer_id product_id ---> id name placed_at quantity name email total_amount price price Write the SQL statements to create these tables --- # Creating Data Write `insert` statements to create the following data ## customers ``` id | name | email ----+-------------+-------------------- 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com 2 | John Doe | test@example.com 3 | Nowhere Man | man@nowhere.com ``` ## products ``` id | name | price -----+-----------------------------+------- 1 | Blueberry Muffin | 2.99 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 3 | Coffee | 3.99 ``` --- # More Data ## orders *HINT: use `now()` to get the current time* ``` id | customer_id | placed_at | total_amount ----+-------------+----------------------------+-------------- 1 | 1 | 2015-06-22 17:35:32.020386 | 2 | 1 | 2015-06-22 17:35:32.020386 | 3 | 2 | 2015-06-22 17:35:32.020386 | ``` ## line items ``` id | order_id | product_id | quantity | price ----+----------+------------+----------+------- 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | ``` --- # Queries Queries are made up of keywords, which I've put in CAPITAL LETTERS in the examples, which is a convention some people follow when writing SQL by hand. The 4 main types are queries are: 1. SELECT - For retrieving data 2. INSERT - For creating new rows 3. UPDATE - For updating existing rows 4. DELETE - For removing rows --- # Select `SELECT` queries are used to retrieve data ```sql SELECT <column_names> FROM <table_name> ``` Use a `SELECT` query to get all of the orders ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders ``` Use `\e` to enter the query using Sublime Text. Once you save the file _(⌘+s)_ and close the tab _(`⌘+w`)_, you will see the result of the query in `psql`: .terminal betastore=# \e id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 (3 rows) betastore=# \e ... You can use `*` in place of column names to get all columns: ```sql SELECT * FROM orders; ``` --- # Where Use the `WHERE` clause to filter the rows that are returned ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders WHERE placed_at > '2013-09-30'; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 (2 rows) A query can be separated on multiple lines and must end with a `;` --- # Limit Use `LIMIT` to control how many rows are returned: ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders LIMIT 1; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+--------------------- 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 (1 row) `LIMIT` can be combined with `WHERE`: ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders WHERE placed_at > '2013-09-30' LIMIT 1; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 (1 row) --- # Order Use `order` to control the order the rows are returned in ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders ORDER BY placed_at desc; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 (3 rows) The opposite of `desc` is `asc`, but it is the default and can be omitted: ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders ORDER BY placed_at; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 (3 rows) --- # Order Can also be combined with WHERE and LIMIT: ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders WHERE placed_at > '2013-09-30' ORDER BY placed_at LIMIT 1; ``` .terminal betastore=# \e id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 (1 row) You can order by multiple columns: ```sql SELECT id, customer_id, placed_at FROM orders ORDER BY customer_id desc, placed_at; ``` .terminal id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+---------------------------- 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 (3 rows) --- # Joins Each order is related to a customer via the the `customer_id` foreign key: .terminal orders customers ------ --------- id id <--- customer_id name placed_at email We want to get data from both of these tables in one query: .terminal customers id | name ----+------------ 1 | Paul Barry 2 | John Doe 3 | Nowhere Man orders id | customer_id | placed_at ----+-------------+-------------------- 1 | 1 | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 2 | 1 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 3 | 2 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 --- # Inner Join Use `JOIN` to combine data from multiple tables: ```sql SELECT c.id as customer_id, o.id as order_id, c.name as customer_name, o.placed_at as ordered_at FROM customers c JOIN orders o on c.id = o.customer_id; ``` .terminal customer_id | order_id | customer_name | ordered_at -------------+----------+---------------+---------------------------- 1 | 1 | Paul Barry | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 1 | 2 | Paul Barry | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 2 | 3 | John Doe | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 (3 rows) Notice Customer 3, Nowhere Man, is not in the result set --- # Outer Join Use `LEFT OUTER JOIN` to include rows where there is no match ```sql SELECT c.id as customer_id, o.id as order_id, c.name as customer_name, o.placed_at as ordered_at FROM customers c LEFT OUTER JOIN orders o on c.id = o.customer_id; ``` .terminal customer_id | order_id | customer_name | ordered_at -------------+----------+---------------+---------------------------- 1 | 1 | Paul Barry | 2013-09-27 00:00:00 1 | 2 | Paul Barry | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823 2 | 3 | John Doe | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245 3 | | Nowhere Man | (4 rows) The value `NULL` is returned for all the columns from the orders table when there is no match --- class: center, middle  --- # IS NULL You can use `IS NULL` to filter down the results to only rows where the column is null ```sql SELECT c.id as customer_id, c.name as customer_name FROM customers c LEFT OUTER JOIN orders o on c.id = o.customer_id WHERE o.id is null; ``` In this case, the effect is that we get customers who have not placed an order: .terminal customer_id | customer_name -------------+--------------- 3 | Nowhere Man --- # Distinct Switching back to an inner join we get a row for each order: ```sql SELECT c.id as customer_id, c.name as customer_name FROM customers c JOIN orders o on c.id = o.customer_id; ``` .terminal customer_id | customer_name -------------+--------------- 1 | Paul Barry 1 | Paul Barry 2 | John Doe Use `distinct` to eliminate duplicates: ```sql SELECT DISTINCT c.id as customer_id, c.name as customer_name FROM customers c JOIN orders o on c.id = o.customer_id; ``` .terminal customer_id | customer_name -------------+--------------- 2 | John Doe 1 | Paul Barry --- # Count Use `count(*)` to count how many records match the criteria: ```sql SELECT count(*) FROM orders; ``` .terminal count ------- 3 (1 row) ```sql SELECT count(*) FROM orders WHERE placed_at > '2013-09-30'; ``` count ------- 2 (1 row) --- # Other Aggregate Functions There are other aggregate functions available like `sum`, `avg`, `min` and `max`. Before we take a look at these, toggle into extended display mode: .terminal betastore=# \x Expanded display is on. Now run this query: ```sql SELECT count(*), sum(price), avg(price), min(price), max(price) FROM products; ``` You will see the following result: .terminal -[ RECORD 1 ]------------- count | 3 sum | 10.73 avg | 3.5766666666666667 min | 2.99 max | 3.99 You can switch back into non-extended display: .terminal betastore=# \x Expanded display is off. --- # Grouping Use `GROUP BY` to group rows that have the same value together, useful for aggregate queries, such as this one that will give you the number of orders each customer has placed. ```sql SELECT count(*) as order_count, customer_id FROM orders GROUP BY customer_id ORDER BY order_count desc LIMIT 10; ``` .terminal order_count | customer_id -------------+------------- 2 | 1 1 | 2 (2 rows) In this example, `GROUP BY` is combined with `ORDER BY` and `LIMIT` to create a top 10 list, but that isn't necessary, you can use `GROUP BY` by itself if you choose. --- # Having If you are looking for all customers with multiple orders, this doesn't work: ```sql SELECT count(*) as order_count, customer_id FROM orders WHERE order_count > 1 GROUP BY customer_id ORDER BY order_count desc; ``` If you want to filter based on the result of an aggregation, use `HAVING` instead: ```sql SELECT count(*) as order_count, customer_id FROM orders GROUP BY customer_id HAVING count(*) > 1 ORDER BY order_count desc; ``` You can use a combination of `WHERE` and `HAVING` to get, for example, all customers with multiple orders since 2014-03-01: ```sql SELECT count(*) as order_count, customer_id FROM orders WHERE placed_at > '2014-03-01' GROUP BY customer_id HAVING count(*) > 1 ORDER BY order_count desc; ``` --- # In You can use `IN` to match multiple values. ```sql SELECT * FROM products WHERE name in ('Muffin', 'Coffee') ``` This example returns all products named `'Smoothie'` or `'Coffee'`: .terminal id | name | price | created_at | updated_at ----+--------+-------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 1 | Muffin | 2.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 3 | Coffee | 3.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 (2 rows) --- # Like You can use `LIKE` to do partial string matches, with `%` as the wildcard character: ```sql SELECT * FROM products WHERE name LIKE '%o%'; ``` This example returns all products with an `o` in their name: .terminal id | name | price | created_at | updated_at ----+----------+-------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.32101 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.32101 3 | Coffee | 3.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 (2 rows) --- # And You can combine multiple conditions together to for a WHERE clause with `AND`: ```sql SELECT * FROM products WHERE name LIKE '%o%' AND price > 3.75; ``` This example returns all products whose name contains an `o` and have a price greater than 3.75: .terminal id | name | price | created_at | updated_at ----+--------+-------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 3 | Coffee | 3.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 (1 row) --- # Or Similar to `AND`, but only one of the conditions has to be met for the row to be included ```sql SELECT * FROM products WHERE name LIKE '%o%' OR price < 3; ``` This example returns all products whose name contains an `o` or have a price less than 3: .terminal id | name | price | created_at | updated_at ----+----------+-------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 1 | Muffin | 2.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 2 | Smoothie | 3.75 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.32101 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.32101 3 | Coffee | 3.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.323369 (3 rows) --- # Nested Conditions You can combine `AND` and `OR` to build more complex queries. Use parentheses to control the precedence. ```sql SELECT * FROM products WHERE price < 3 AND (name = 'Muffin' OR name = 'Coffee'); ``` This example returns all products that have a price less than 3 and are named either `Muffin` or `Coffee`: .terminal id | name | price | created_at | updated_at ----+--------+-------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 1 | Muffin | 2.99 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.317279 (1 row) --- # Subqueries You can use the results of one query to filter the results of another using a subquery: ```sql SELECT * FROM customers WHERE id in (SELECT customer_id FROM orders); ``` This example will return all customers who have placed an order: .small[ .terminal id | name | email | created_at | updated_at ----+------------+--------------------+---------------------------+--------------------------- 1 | Paul Barry | mail@paulbarry.com | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.29229 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.29229 2 | John Doe | test@example.com | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.30248 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.30248 (2 rows) ] Subqueries can often be expressed as a join instead, I recommend that whenever possible --- # Insert You can create new record using insert: ```sql INSERT INTO customers (name, email, created_at) VALUES ('New Guy', 'new@example.com', now()); ``` You can see the record was created and the id was auto-generated even though we didn't provide a value for it: ```sql SELECT * FROM customers ORDER BY id desc LIMIT 1; ``` .terminal id | name | email | created_at | updated_at ----+---------+-----------------+----------------------------+------------ 4 | New Guy | new@example.com | 2014-03-06 05:22:03.000289 | (1 row) --- # Update We can change that record with an UPDATE ```sql UPDATE customers SET name = 'New Person', updated_at = now() WHERE id = 4; ``` After we run that statement, you can see the record has been updated if you select it again: ```sql SELECT * FROM customers ORDER BY id desc LIMIT 1; ``` .small[ .terminal id | name | email | created_at | updated_at ----+------------+-----------------+----------------------------+---------------------------- 4 | New Person | new@example.com | 2014-03-06 05:22:03.000289 | 2014-03-06 05:23:16.854682 (1 row) ] --- # Delete We can remove the record from the database with a DELETE: ```sql DELETE FROM customers WHERE id = 4; ``` Now we can see that the most recent user is back to Nowhere Man: ```sql SELECT * FROM customers ORDER BY id desc LIMIT 1; ``` .small[ .terminal id | name | email | created_at | updated_at ----+-------------+-----------------+---------------------------+--------------------------- 3 | Nowhere Man | man@nowhere.com | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.30497 | 2014-03-06 09:47:20.30497 (1 row) ] --- # Exporting to CSV One thing that you might find yourself needing to do is to export the data to CSV, so you can open it in a spreadsheet, share it with other people who don't have direct access to the database, etc. Postgres allows you to use `COPY` to do this. For example, run this command from `psql` to copy the data from the orders table to a CSV file: .terminal betastore=# COPY orders TO '/tmp/orders.csv' CSV; COPY 3 betastore=# \q The file looks like this: .small[ .terminal $ cat /tmp/orders.csv 1,1,2013-09-27 00:00:00,,2014-03-06 09:47:20.351343,2014-03-06 09:47:20.351343 2,1,2014-03-06 09:47:20.374823,,2014-03-06 09:47:20.375697,2014-03-06 09:47:20.375697 3,2,2014-03-06 09:47:20.380245,,2014-03-06 09:47:20.381082,2014-03-06 09:47:20.381082 ] You can now open this file in a spreadsheet program like Excel, Numbers, Libre Office, Google Docs, etc. You can also use `COPY` to load data into a table from a CSV file. For more information on how to do that, read [the documentation for the COPY command][copy]. One thing to note is that the `COPY` command is not part of the SQL standard and will not work in other databases like MySQL, SQLite, Oracle, SQL Server, etc. Each of those databases have their own tools for exporting data. [copy]: http://www.postgresql.org/docs/9.3/static/sql-copy.html --- # Summary * Use **SELECT** with **WHERE**, **ORDER**, **LIMIT** to retrieve data * Use **JOIN** to combine data from multiple tables * Use **GROUP BY** to aggregate data, **HAVING** to filter results * Use `count()`, `avg()`, `sum()`, `min()` and `max()` * Use **INSERT** to create new rows * Use **UPDATE** to modify existing rows * Use **DELETE** to remove existing rows * Use **COPY** to export data to CSV